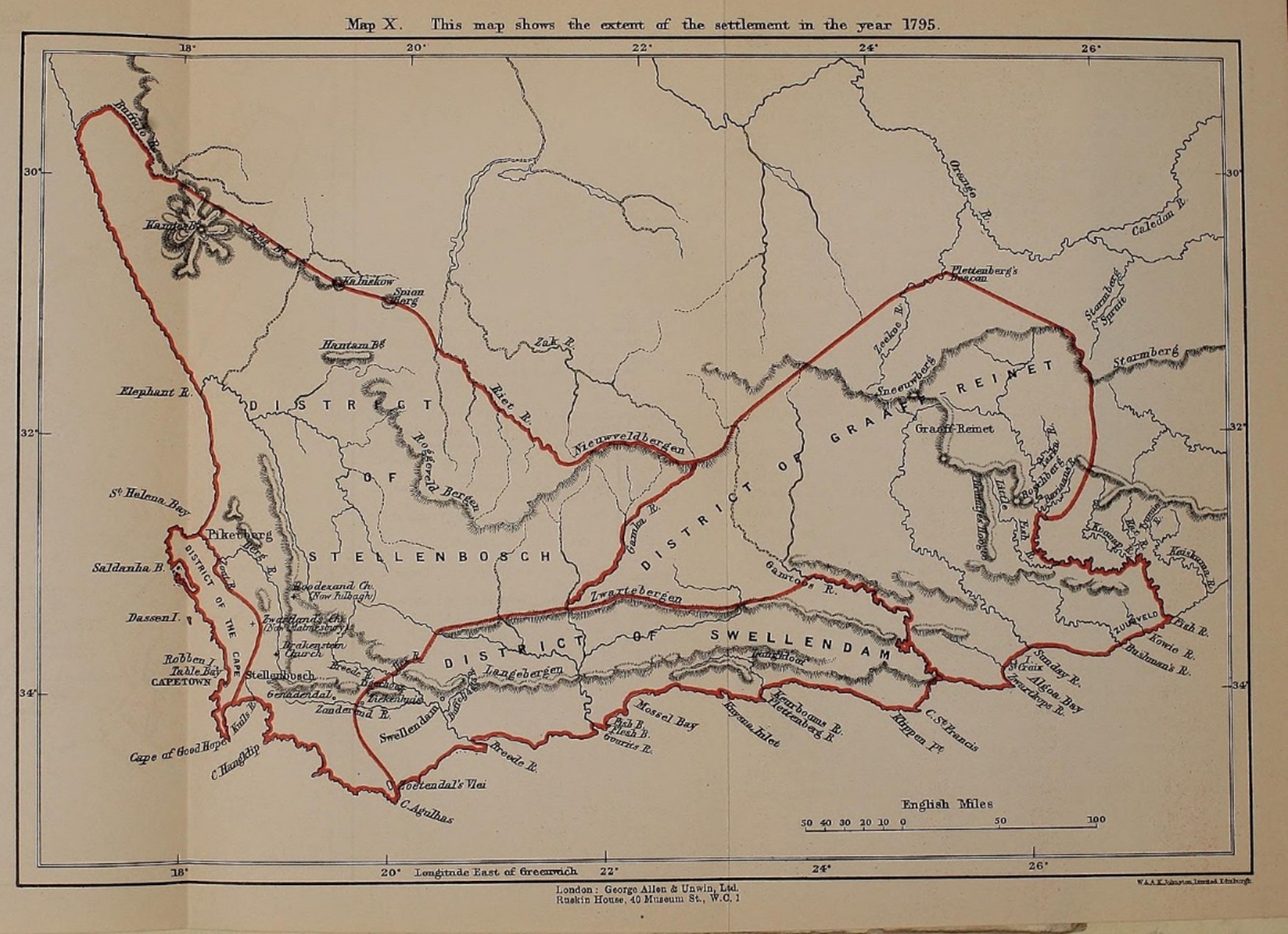

Johannes Christoffel Krog South Africa 1795

1795 Battle of Muizenberg

The Cape Colony, also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was under VOC rule from 1652 to 1795. The VOC lost the colony to Great Britain following the 1795 Battle of Muizenberg.

The Dutch colony at the Cape, established and controlled by the United East India Company in the seventeenth century, was at the time the only viable South African port for ships making the journey from Europe to the European colonies in the East Indies. It therefore held vital strategic importance, although it was otherwise economically insignificant. In the winter of 1794, during the French Revolutionary Wars, French troops entered the Dutch Republic, which was reformed into the Batavian Republic.

In response, Great Britain launched operations against the Dutch Empire to use its facilities against the French Navy. The British expedition was led by Vice-Admiral Sir George Keith Elphinstone and sailed in April 1795, arriving off Simon’s Town at the Cape in June. Attempts were made to negotiate a settlement with the colony, but talks achieved nothing and an amphibious landing was made on 7 August. A short battle was fought at Muizenberg, and skirmishing between British and Dutch forces continued until September when a larger military force landed. With Cape Town under threat, Dutch governor, Abraham Josias Sluysken, surrendered the colony.

The VOC Makassar

The VOC Makassar was a Dutch East India Company vessel built in 1787 and actively used in the company’s far-flung maritime trade network until its dramatic capture during the turbulent years of the French Revolutionary Wars. As Europe’s geopolitical landscape shifted rapidly after the Dutch Republic transformed into the Batavian Republic—an ally of revolutionary France—the British seized every opportunity to undermine Dutch commercial power. In this context, ships like the Makassar became targets for the increasingly assertive Royal Navy. The capture occurred near the remote island of St Helena, a vital resupply stop en route between Europe and the East Indies, where tensions boiled over into open conflict between British and Dutch interests. During her second homeward journey, the Makassar, sailing unaware that the political tides had turned decisively against her, was intercepted by the British. Under the command of the renowned explorer George Vancouver aboard HMS Discovery, the British naval force took the ship as a prize. On July 16, 1795, HMS Discovery departed from St Helena with the Makassar in tow, bound for the Thames in London—a tangible assertion of British naval dominance and a blow to the VOC’s global trading empire.

The events surrounding this capture illustrate not only a moment of maritime conquest but also the broader strategic imperatives at work during this tumultuous era. The British, capitalizing on the instability within the Dutch state, systematically targeted VOC vessels to disrupt the lucrative spice and goods trade that had long been the backbone of Dutch colonial power. VOC records indicate that the Makassar had served faithfully in its role for over a decade before the sudden reversal of fortune. Its capture was emblematic of a period in which ships were more than mere vessels; they were symbols of national wealth, prestige, and military might. The seizure at St Helena also involved the removal of crew members who, in the fraught atmosphere of war, were often suspected of divided loyalties or even of being politically undesirable.

British records and maritime archival research reveal that the captured Makassar was not simply relegated to obscurity but was taken as a prize to be integrated into the British fleet, thereby denying the VOC a valuable asset while bolstering British maritime strength. The ship’s redirection to London represented a dual victory: it not only symbolized the shifting balance of power at sea but also demonstrated the ruthless efficiency with which the Royal Navy operated against its rivals. In many respects, the capture of the VOC Makassar encapsulates the intersection of commercial ambition, naval warfare, and political intrigue that defined the late 18th century. It serves as a historical case study of how rapid and transformative changes in global politics could turn the tide of fortune for entire empires, with individual ships playing pivotal roles in that evolving narrative.

As a direct consequence of the English invasion and the surrender of the Dutch Colony, on the 14th of June 1795, the Makassar was taken by the English off St. Helena where Johannes Christoffel Krog was “removed” from the Makassar[1].

It would seem therefore that his arrival at the Cape Colony was entirely unplanned and due to the circumstances, he actually had little choice but to settle in the Cape.

The Makassar was captured by the explorer George Vancouver aboard the HMS Discovery during her second homeward journey. The circumstances, briefly, were that the HMS Discovery, and the brig Chatham, captured the Makassar, which sailed in, unaware that the newly established Batavian Republic was at war with Great Britain. On July 16, HMS Discovery left St Helena with the Makassar. The Makassar is said to have sailed to the Thames in London.[2]

VOC records explained[3] that people were removed by the English authorities, which were often the case in English ports, because of suspicions that they were English and therefore prohibited from signing on foreign ships. Given that he was of possible German descent, and working on a Dutch ship for the VOC, it is more plausible that Johannes Christoffel Krog was removed for political reasons.

VOC records for Johannes Christoffel Krog shows that he did not send any money (maximum of 3 months pay) to first degree (closest) relatives, such as parents, called a month certificate but did have a debenture or forward transfer up to a maximum of 300 guilders[4].

[1] https://www.openarch.nl/ghn:6df51ba4-3432-41e4-a2fe-8010b1406133 ![]()

[2] de VOCsite – https://www.vocsite.nl/schepen/detail.php?id=10646 ![]()

[3] Nationaal Archief (Netherlands), Dutch East India Company, archive 1.04.02, inventory number 6839, folio 38 – https://www.openarch.nl/ghn:6df51ba4-3432-41e4-a2fe-8010b1406133 ![]()

[4] Ibid.